If you’ve lived in the Southeast for a good portion of your life (as our team has), chances are you’ve been exploring Appalachia and the Blue Ridge range for years.

Maybe you’ve visited state parks in North Georgia and North Carolina, hiked to various waterfalls, soaked in the scenery atop majestic mountains, or taken a road trip on the Blue Ridge Parkway.

But how much do you actually know about the rich Appalachian culture of the Blue Ridge region?

Appalachia is a vast area that stretches from southern New York to north Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. It encompasses 420 counties across 13 states, spans 205,000 square miles, and is home to some 25 million people.

Appalachian culture is a way of life that dates back to the 1700s, when Europeans began immigrating to America in greater numbers.

Although it started in the states of North Carolina and Virginia, the culture spread quickly to other states after the Revolutionary War, as settlers began to explore outside the original 13 colonies.

The culture of Appalachia consists of art and crafts, food, myths and folklore, multiple ethnic influences (including African, German, and Native American), and an array of stereotypes.

It is a culture that essentially defined “Americana” as we know it today. And if your family has roots in Ireland, Scotland, or Germany, chances are good it’s a core aspect of your personal genetic heritage.

Read on to learn more about the history of Appalachian culture and people, including a look at how some of the most common stereotypes came to be.

READ MORE: 30 Fascinating Blue Ridge Mountains Facts

Appalachian Culture Guide

- Appalachian History

- Appalachian People

- Poverty in Appalachia

- Appalachian Culture

READ MORE: 20 Incredible Places To See the Blue Ridge Mountains in Fall

A Brief Appalachian History

Native Americans first began to gather in the Appalachian Mountains some 16,000 years ago. Cherokee Indians were the main Native American group of the Southern Appalachian and Blue Ridge region, but there were also Iroquois, Powhatan, and Shawnee people.

The arrival of enslaved Africans in the area dates back to the 16th century. These two groups both had a tremendous influence on the culture of Appalachia.

When European immigration began in the 1700s, the settlers claimed lands from the coast west into the Appalachian Mountains.

Many of the newcomers who moved deep into rural Appalachia were Scotch-Irish and German, bringing the traditions of their native countries with them.

At that time, there were 50+ Cherokee towns and settlements in the area connected by a system of foot trails, many of which later became wagon roads built by Cherokee companies.

The growing need for land for immigrants led to countless bloody battles and, ultimately, treaties with the Native American tribes.

Unfortunately, these treaties removed nearly all of the Cherokee and other native groups from the region, as the government forced them to move west on the tragic Trail of Tears.

READ MORE: 40 Fascinating Facts About Cherokee Culture & History

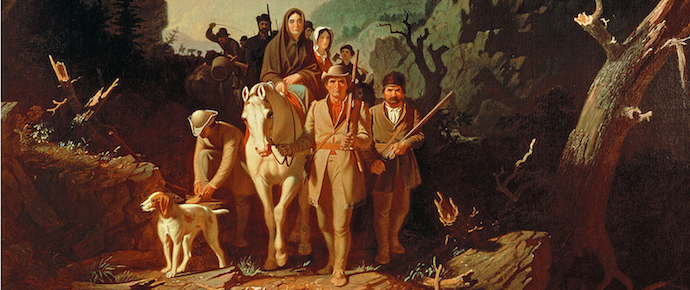

The wilderness of Appalachia became a frontier for exploration and living. Daniel Boone, whose 1775 expedition through Virginia’s Cumberland Gap into Kentucky established the route for settlers moving west, became the first folk hero of America’s pioneer era.

Eventually disagreements grew between the wealthy elites living in the lowlands and along the coast, and the more rural people of the Appalachian backcountry.

The brutality of the Civil War only served to reinforce the resentment many rural people had for government authority and outsiders.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, stereotypes of Appalachian people began to take root.

The mountainous region experienced both a Northern economic boom and increased conflict during this period. The rapid growth of the logging industry caused environmental degradation, which led to greater Appalachian conservation efforts.

This gave us numerous protected wilderness areas, including Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountains National Park, as well as the George Washington & Jefferson, Chattahoochee-Oconee, and Pisgah National Forest.

It also led to the creation of other beloved national treasures, including the Blue Ridge Parkway, the Appalachian Trail, and North Carolina’s Mountains-to-Sea Trail.

READ MORE: 20 Best Blue Ridge Parkway Overlooks in NC & VA

Appalachian People

Appalachia was comprised of a complex mix of ethnic groups. The one common trait that bound them all together is that they were used to working hard and being self-reliant.

So they had the intestinal fortitude it took to rough it out in the backcountry of the rugged Blue Ridge mountains.

Scots-Irish “Hillbillies”

About 90% of Appalachian settlers in the 18th and 19th centuries were Scots-Irish (a.k.a. Scotch-Irish) descendants of Ulster Protestants, whose ancestors had migrated to northern Ireland from the Scottish lowlands.

Many had been supporters of William of Orange, the protestant King of Scotland, England, and Ireland, who was affectionately known as “King Billy” among the Scots.

When former King James II invaded Ireland in 1689, William’s followers, known as “Billyboys,” hid out in forests along the hills for sneak attacks upon the enemy.

When their ancestors came to America, New England was already full of British settlers, so the “hillbillies” settled into the wilderness of the Appalachian Mountain range.

Many started out in Virginia and North Carolina, eventually spreading into North Georgia and east Tennessee.

They were largely poor, humble, and fiercely self-reliant, with an innate distrust of government after decades of fighting the English and Catholics.

This is where Appalachian cultural stereotypes such as family loyalty, rebellion against authority, and passion for self-defense gave rise to the image of hillbillies as wild, reclusive mountain men.

READ MORE: Appalachian Folklore, Monsters and Superstitions

Germans (a.k.a. Pennsylvania Dutch)

German immigrants (who were often referred to as Dutch because they came from “Deutschland”) were another group that had a huge influence on Appalachian culture.

They primarily settled in Pennsylvania and Virginia, bringing with them German foods such as apple butter and sauerkraut, and traditions such as chinked-corner cabins.

Their cultural identity was so strong that they didn’t assimilate very well. Instead, they often had their own German schools and churches.

You can still feel their influence today in Appalachian Alpine towns such as Little Switzerland NC and Helen GA.

But the Germans were treated considerably less harshly in America than the Scotch-Irish and Italian immigrants were, primarily because they looked more like the British colonists.

But where the Scots-Irish in Appalachia tended to keep to themselves and were generally too poor to own slaves, the Germans often discriminated against African Americans.

And their settlement was much more directly impactful on the displacement of Native American populations.

Another interesting, but rarely discussed Appalachian cultural influence was that of the Scandinavians, particularly people from Finland and Sweden.

They brought with them woodworking skills from Northern Europe, which gave rise to the log cabin so ubiquitous in the Blue Ridge area today.

READ MORE: The 15 Best North Carolina Mountain Towns to Visit

African Americans

Although Appalachia is often thought of as a rural, primarily Caucasian region, African Americans have inhabited the area for hundreds of years. In fact, by 1860 an estimated 10% of the Appalachian region’s population was black.

As white settlers moved into the Appalachian Mountains, so did Africans, both free and enslaved.

Elite whites and Cherokee people alike held Africans in enslavement in southern Appalachia, but the mountain landscape did not naturally lend itself to the large plantations of the Deep South.

In fact, the majority of Appalachian people were not slave holders. Folks in what became West Virginia even split off and joined the Union after Virginia voted to join the Confederacy.

There was an active Underground Railroad that ran through Appalachia, from Chattanooga north to Pennsylvania.

America’s early pioneer era saw whites, blacks, and Indians all living close together in the Appalachian range.

This gave rise in the early 19th century to a multiracial group known as the Melungeons, who had African, European, and Native American ancestry.

But the African influence on Appalachia persists even today. The banjo– a stringed instrument central to bluegrass and other forms of Appalachian music– originated in Africa.

The people of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora also introduced foods such as sorghum cane, sweet potatoes, blackeyed peas, watermelon, and peanuts into Appalachian cuisine.

Kentucky-based writer Frank X Walker coined the term “Afrillachia” in the 1990s as a means to bring awareness to the cultural influence of African Americans in Appalachia.

And the Black in Appalachia website and podcast are great resources for learning more about this hidden history.

READ MORE: The Top 20 Blue Ridge Mountain Towns in GA & NC

Poverty in Appalachia

History of Poverty in Appalachia

The prevalence of Appalachian poverty came to broader attention in 1940, when James Still’s novel River of Earth (which documented Appalachia during the Great Depression) was published.

But by that point, the people of Appalachia had already been suffering for decades.

In retrospect, it seemed that the original settlers’ core values of freedom, self-reliance, and a unique inidividual identity eventually put Appalachian people at odds with the advancements of modern life.

Isolation, and a fear of losing touch with their traditional values, led to crippling poverty.

Even in the 1960s and 70s, many people in Appalachia were still living without basic necessities such as electricity or indoor plumbing. Hunger and a lack of basic hygiene were not uncommon.

In 1965, after President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a “War on Poverty,” the Appalachian Regional Commission was launched.

Originally founded by John F. Kennedy, this federal-state partnership focused on helping Appalachian people create opportunities for self-sustaining economic development and improved quality of life.

The ARC has worked for 55 years to bring the region into socioeconomic parity with the rest of the nation. It defined the region of Appalachia, created educational opportunities for the people who lived there, and invested in economic development projects benefiting all 420 counties.

READ MORE: The 20 Best Western North Carolina Waterfalls for Hiking

Appalachian Stereotypes

We all know the stereotypes of Appalachian people as “poor white trash.”

Inbreds, yokels, hicks, and rednecks are just a few of the common slurs that have been used over the last century (though some country folk reclaimed the last one as a point of pride, seeing it as a reflection of their humble lifestyle and hard work ethic).

These stereotypes are not only largely incorrect, but they’re also highly offensive to the people of Appalachia. Especially when the region has been such a rich melting pot of ethnicities and cultures from the very beginning.

African-Americans and Latinos are the largest minority groups in the region, but Appalachia’s 20th century coal revolution brought in many other cultures that added to the diversity of the region.

The reality is that Appalachia was isolated while the rest of the country was modernizing, leaving them behind in a sense. As a result, they were less educated, less well nourished, and less wealthy than people who lived in major metroplises and their suburbs.

Their traditional way of life, which involved living off the land, made the people of Appalachia appear as hillbilly farmers to outsiders. When in fact they were really the sort of hard-working, salt-of-the-earth people who helped make the United States what it is today.

Even now, there are still literacy issues, health problems, and other issues related to poverty that plague parts of Appalachia. There remains an often stark income inequality between the tourists that visit the region and the people who actually live there.

One prime example of this is the Biltmore Estate, which was built by the elite Vanderbilts to cater to their upper class friends even as the rest of Appalachia grappled with poverty.

Yet still, with help from the ARC and the benefits of tourism revenue, the people of the region are finding ways to improve their circumstances by commodifying the very things that make Appalachian culture so uniquely American.

READ MORE: Downtown Asheville, NC History: From Biltmore to the 21st Century Boom

Appalachian Culture

Appalachian Art & Crafts

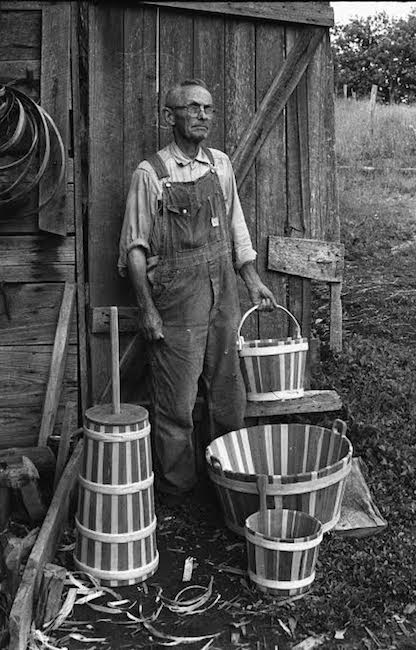

We’ve reiterated multiple times throughout this story how important self-sufficiency has always been to Appalachian people.

So perhaps it’s no surprise that arts and crafts in Appalachia originally came out of necessity.

Handmade quilts, coverlets, pottery, wood carvings, and woven baskets were beautiful and often displayed in the home. But they also served a more functional purpose than mere décor.

The use of natural dyes and natural materials (as well as whatever scraps of fabric they had on hand) resulted in unique and colorful pieces that brought art to the homes of Appalachia.

There was a push that started back in the 1920s to preserve traditional Appalachian arts and crafts. But technology and market demand has influenced both the process and result of these works over the course of the last century.

The Appalachian Mural Trail, which goes through the Blue Ridge National Heritage Area and the Appalachian Mountains, is a movement to create outdoor murals that depict Appalachian culture.

Travelers can also visit the Appalachian Craft Center in Asheville, the Southern Highland Craft Guild’s Folk Art Center off the Blue Ridge Parkway in Asheville, and the Appalachian Center For Craft at Tennessee Tech to learn more about the history and evolution of Appalachian art.

READ MORE: Asheville River Arts DIstrict Galleries & Restaurants Guide

Appalachian Folklore

Christianity has been the predominant religion in Appalachia ever since European immigration to the area began in the 1700s.

These Christian influences blended with traditional European (i.e. pagan) and Native American spiritual beliefs, creating a unique blend of folklore and mythology in Appalachia.

The Cherokee brought their reverence for nature and knowledge of native plants, herbs, and animals, influencing local practices for centuries. Cherokee folklore influenced Appalachian storytelling in the way it dramatically characterized animals or other inanimate objects in nature.

Old English, Scottish, Irish, and German (see: the Brothers Grimm) fairy tales came from Europe. These fairy tales, combined with regional events, also shaped Appalachian folklore.

There are “Jack Tales,” which usually revolve around a single, hard-working figure. Jack is usually lazy or foolish, but through cleverness and tricks he succeeds in his quest. Some examples of old English Jack Tales are “Jack & the Beanstalk” and “Jack Frost.”

In Appalachia, Jack is likely to be a sheriff or a more common man. And, like most Appalachian folklore, these Jack Tales were passed down orally, rather than being written down.

Another popular type of folktale in Appalachia involves regional heroes, such as Davy Crockett, Daniel Boone, Johnny Appleseed, and John Henry.

These stories are based on real figures and events, but they take on folklore status as the stories are exaggerated for dramatic effect.

Murder and stories of the macabre are also popular in Appalachia’s folk ballads. Murderers like John Hardy, victims such as Omie Wise, and specters like the Greenbriar Ghost are all common horrific stories that became lasting oral traditions.

But the most popular Appalachian folktales involve mysterious creatures such as Bigfoot and the Mothman. B

both have garnered a wealth of attention, including the 2002 film The Mothman Prophecies, the TV show Finding Bigfoot, and the Expedition Bigfoot Museum near Blue Ridge, GA.

READ MORE: Visiting Expedition Bigfoot Museum in Cherry Log, GA

Appalachian Literature

Storytelling plays an essential role in Appalachian culture, which was historically passed down orally. These oral traditions no doubt influenced later literature.

Early literature on the region included observations by famous icons, like Thomas Jefferson and Davy Crockett. But for many years it was primarily outsiders giving their perspectives on the wilderness of Appalachia.

Then in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, more and more Appalachian authors started giving their perspectives on their region and its cultural traditions.

Some famous examples are James Still’s River of Earth, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, James Agee’s A Death in the Family, Charles Frazier’s Cold Mountain, Fannie Flagg’s Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe, and Homer Hickam Jr’s Rocket Boys.

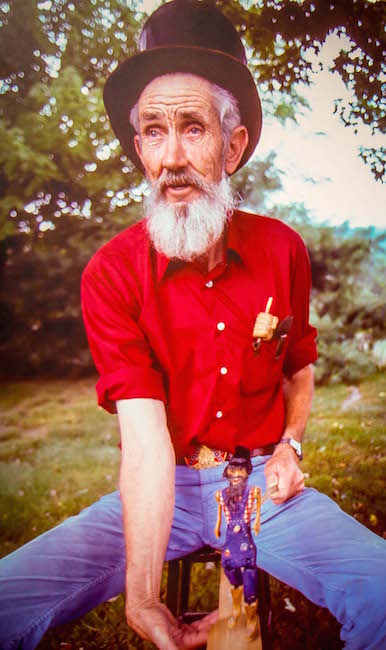

But the Foxfire books were arguably the most influential literature in terms of encouraging American appreciation of Appalachian culture and its traditional way of life.

An ongoing series whose first volume was published in 1972, these books edited by Eliot Wigginton have introduced millions of people to the traditional wisdom of these mountains.

Through interviews with old-timers (including the world-famous Aunt Arie), the books teach creative self-sufficiency and help preserve the stories, crafts, and customs of Southern Appalachia.

If you have any interest whatsoever in building log cabins, mountain crafts and foods, planting by the signs, hunting tales, faith healing, or moonshining, they are truly a must-read. We’ll have a more in-depth story about the Foxfire Museum & Heritage Center in Clayton, GA coming soon!

READ MORE: The Best Things to Do in Clayton, GA

Appalachian Food

As you would probably expect, traditional Appalachian food largely consists of the things local people found in nature– wild plants, core crops, and hunted animals.

Some common Appalachian food staples include corn (for making cornbread), apples, home grown vegetables, flour (for biscuits), grits, and stews made with rabbit or chicken.

Preserving and canning fruits and vegetables is a major component of Appalachian food culture. As a child I remember going to Asheville every year with my family to get fresh green beans and peaches for making preserves.

It’s also interesting to explore the origins of some common Appalachian cooking staples. Corn, beans, and squash were called “the three sisters” and grown together by Native Americans. Corn grew high, squash closer to the ground, and beans wrapped around the cornstalks.

The Scots-Irish immigrants brought their agricultural practices to make these and other ingredients more widely available. African-Americans brought sorghum cane, sweet potatoes, red peppers, okra, blackeyed peas, watermelon, and peanuts.

What all of these various ethnic groups’ foods have in common are homegrown (or wild foraged) simple, natural ingredients.

If you’re not from the Appalachian region, do yourself a favor and try dishes like Chow Chow, Skillet Cornbread, Chicken & Dumplings, and Country Ham with Red Eye Gravy.

If you like to cook at home, the Southern Foodways Alliance Community Cookbook is a great source for traditional Appalachian recipes.

READ MORE: The 10 Best Restaurants in Blue Ridge GA

Appalachian Music & Dance

For many of us who grew up in the South, Appalachian music was the first aspect of the culture we were introduced to.

Over the last 100+ years of audio recording, the sounds of bluegrass and country music have carried across the USA and around the globe.

As with everything else, the music of Appalachia is a combination of cultural influences. The high, lonesome yearning of English and Scottish ballads, the uptempo rhythms of Scottish and Irish fiddle music, the rhythmic syncopation of African banjo, and the minor key melancholy of the blues.

Commercial recordings in the 1920s solidified Appalachia’s influence on the bluegrass, country, and folk music now collectively referred to as “Americana.”

Legendary acts like the Carter Family, Fiddlin’ John Carson, Dock Boggs, Jean Ritchie, Bascom Lamar Lunsford, and Fiddlin’ Doc Roberts defined the sound of American folk music that still resonates stronger than ever today.

This music is often accompanied by mountain dancing, which is a mixture of Scottish, Irish, English, and Dutch folk dances combined with African and Native American traditions.

Clogging, flatfoot dancing, and square dancing are three of the more popular dancing styles in Appalachian history. Clogging strictly follows the syncopated rhythms of the music, while flatfoot dancing allows the dancer a bit more freedom of expression.

Square dancing is still very popular in parts of Appalachia today. The only one of these dances that requires a partner, it evolved from ancient social dancing in Europe.

Attempts to preserve these Appalachian cultural traditions began in the 1950s, with the American folk music revival launched by the release of Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music.

It once seemed as if these aspects of Appalachian culture might be lost forever once the Great Depression generation passed on. But today these traditions are celebrated by locals and visitors alike, with tourism providing a hopeful future for the region. –by Sonny Grace Bray & Bret Love

Comments are closed.