[Updated on 7/20/21]

Though most Georgia residents have never heard of it, the New Echota Historic Site in Calhoun GA is one of the most important indigenous sites in the United States.

In 1825, the Cherokee Nation established New Echota as its capital, building the “New Town” right at the headwaters of the Oostanaula River.

In 10 years, the town became home to the first Indian language newspaper, a legal case that went all the way to the US Supreme Court, the signing of the New Echota Treaty (which relinquished all tribal lands east of the Mississippi River), and the beginning of the Trail of Tears.

Although the original town disappeared for more than a century, the site was designated as the New Echota National Memorial in 1930.

A 1954 archaeological excavation found more than 1700 historical artifacts there, including the remains of many buildings and the type syllabary that was used to print the Cherokee Phoenix, the first indigenous tribal newspaper.

Reconstruction of the town of New Echota began as a state park in 1957, and was opened to the public in 1962. In 1973, the Department of Interior designated the park as a National Historic Landmark, the highest recognition in the US.

Read on for our in-depth guide to exploring the New Echota Historic Site, which includes 12 original and reconstructed buildings, a historical museum with excellent interpretive exhibits, and two lovely nature trails for hiking.

READ MORE: 101+ Things to Do in North Georgia

New Echota Historic Site Info

ADDRESS: 1211 Chatsworth Highway NE (a.k.a. GA-255), Calhoun, GA 30701

PHONE: 706-624-1321

HISTORIC SITE HOURS: Tuesday– Saturday 9 AM – 5 PM; Sundays 1 PM– 5 PM. Closed on Sundays from December through March, as well as Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years Day.

ENTRY FEES/PASSES: Adults (18–61) $7.00; Seniors (62+) $6.50; Youth (ages 6–17) $5.50; Kids 6 and under free.

OFFICIAL WEBSITE: GA State Parks

DIRECTIONS FROM ATLANTA: Take I-75 N to exit 317 for GA-225/Chatsworth Highway toward Chatsworth. Turn right onto GA-225 N/Chatsworth Rd NE, and you’ll see the Historic Site on your right in approximate 0.7 miles.

DIRECTIONS FROM CHATTANOOGA:Take I-75 S to exit 317 for GA-225/Chatsworth Highway toward Chatsworth. Turn left onto GA-225 N/Chatsworth Rd NE, and you’ll see the New Echota Historic Site on your right in approximate 0.9 miles.

READ MORE: 40 Fascinating Facts About Cherokee Culture & History

Want to explore more of the best North Georgia State Parks?

Check out these great guides!

Things to Do at James H Floyd State Park in Summerville GA

Things to Do in Moccasin Creek State Park

Things to Do in Black Rock Mountain State Park

Things to Do in Unicoi State Park and Lodge

Things to Do in Vogel State Park

The 15 Best North Georgia State Parks & Historic Sites

The History of New Echota

Located in Calhoun GA at the confluence of the Coosawattee and Conasauga rivers, the 200-acre New Echota Historic Site had been used by indigenous tribes for thousands of years before it became the capital of the Cherokee Nation in 1825.

Originally known as Gansagi, the historic site was later named after the Overhill Cherokee town of Chota, which was one of several important towns along the lower Little Tennessee River.

Chota had been the de facto capital of the Cherokee Nation before increasingly intense conflicts with European settlers forced them to move south to Ustanali.

Ustanali translates as “New Town,” a name that is still used for the unincorporated community around the historic state park. The area was also known among Appalachian settlers as “The Fork,” due to the confluence of the rivers.

The newly organized Cherokee Nation government council began meeting in New Echota by 1819, constructing a two-story Council House as well as a Supreme Court building for settling legal matters.

Soon there were private residences, stores, a ferry, and other buildings built in the outlying areas around New Echota, as well as the print shop for the Cherokee Phoenix, the first ever Indian-language newspaper.

READ MORE: The 15 Best Historic Sites in Georgia

Created in 1827, the paper was run by writer/editor Elias Boudinot (born Gallegina Swati), a prominent Cherokee leader with mixed ancestry who believed that assimilation into anglo-European culture was crucial to the Cherokee people’s future.

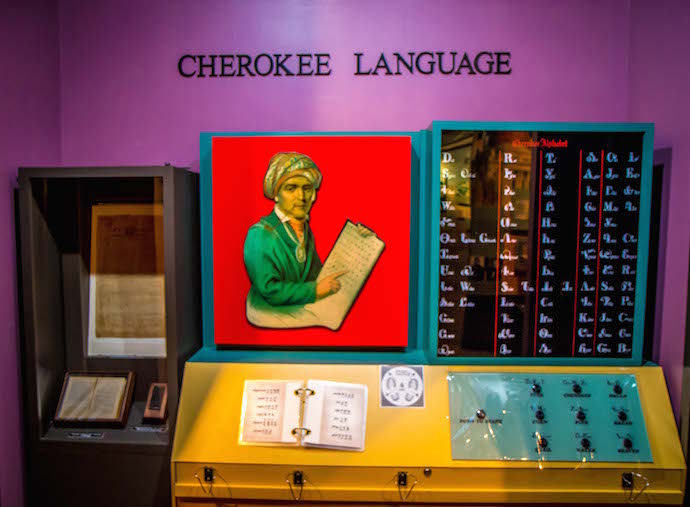

Local missionary Samuel Worcester (best known for translating the Bible into Cherokee) set up the print shop, using the new Cherokee syllabary that was created by Sequoyah in 1821. This was the first written language ever created for America’s indigenous people.

New Echota drew hundreds of people to the Cherokee Council meetings, with tribe members coming on foot and horseback to attend lively social gatherings.

But by 1832, when Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, the state of Georgia had begun to grant Cherokee land to white settlers (many of whom were attracted by the discovery of gold in Dukes Creek) in the Sixth Land Lottery.

The tribe refused to give up, taking their case to the US Supreme Court (and winning). But the Georgia Guard began evicting them anyway, and by 1834 New Echota had been turned into a ghost town.

READ MORE: The Appalachian Culture & History of the Blue Ridge Mountains

The Treaty of New Echota

By the 1820s, the Cherokee Nation claimed approximately 7.8 million acres of land in what is now eastern Tennessee, eastern Alabama, western North Carolina and north Georgia.

The tribe adopted a constitution at New Echota in July of 1827, hoping it would protect them from Georgia’s attempt to claim their lands.

But the 1828 national election, in which Andrew Jackson became president, sealed their fate. Jackson wanted all the southeastern tribes to move west, and Georgia’s legislature took his election as a mandate to evict indigenous tribes.

In December of 1828, the Georgia State legislature passed a bill saying the Cherokee and Creek Indians would be under the jurisdiction of state law.

Five years later, in a speech to Congress, Jackson said, “[these] tribes cannot exist surrounded by our citizens… They have neither the intelligence, the industry, the moral habits, nor the desire to improvement, which are essential to any favorable change in their condition.”

By this time, Cherokee leaders were divided. On one side was Chief John Ross, whose majority “National Party” advocated resistance. On the other was the “Treaty Party,” led by Major Ridge, his son John, and his nephew Elias Boudinot.

Also known as the Ridgeites, this group of less than 500 Cherokee people was a very vocal minority. They believed it was smarter to negotiate with the US government to cede their Georgia lands in exchange for a cash settlement and 7 million acres of land west of the Mississippi River, which would be known as Indian Territory.

In a gesture of compromise, Ross offered to accept a $20 million settlement for the tribe’s Georgia lands, but the government counter-offered at $5 million. The Cherokee council met in October of 1835 at Red Clay, Tennessee, and followed Ross’ advice to reject the offer.

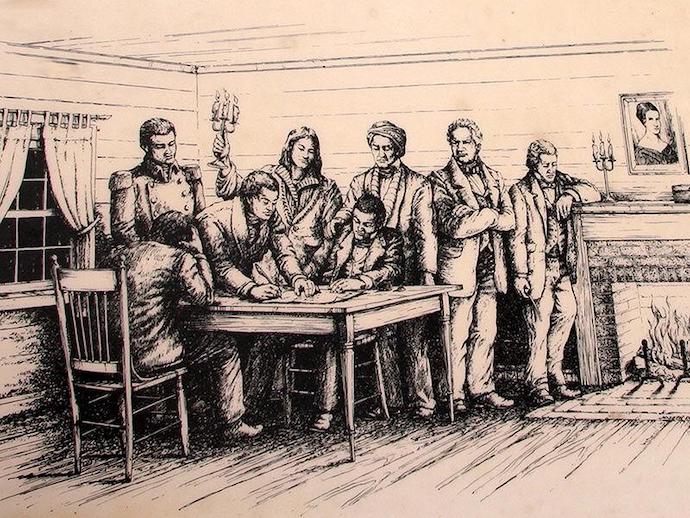

But the Ridgeites and government negotiator John F. Schermerhorn held a similar council at Boudinot’s home in New Echota. Word was spread throughout the Cherokee Nation that anyone not in attendance would be assumed to be in favor of any treaty negotiated there.

On December 29, 1835, the New Echota Treaty was signed by Major Ridge, John Ridge, Andrew Ross (John’s brother), Elias Boudinot, and 17 other tribal leaders. Despite objections from John Ross– the longest-running leader of the Cherokee Nation– the treaty was ratified by the US Senate. Most Cherokees still consider this treaty fraudulent.

In 1838, under the command of Winfield Scott, the US Army began the removal of the Cherokee from the state of Georgia. New Echota’s Fort Wool served as a holding area, from which the Cherokee people were forced to make the arduous exodus west along what became known as the Trail of Tears.

READ MORE: The 20 Best Hiking Trails in North Georgia Bucket List

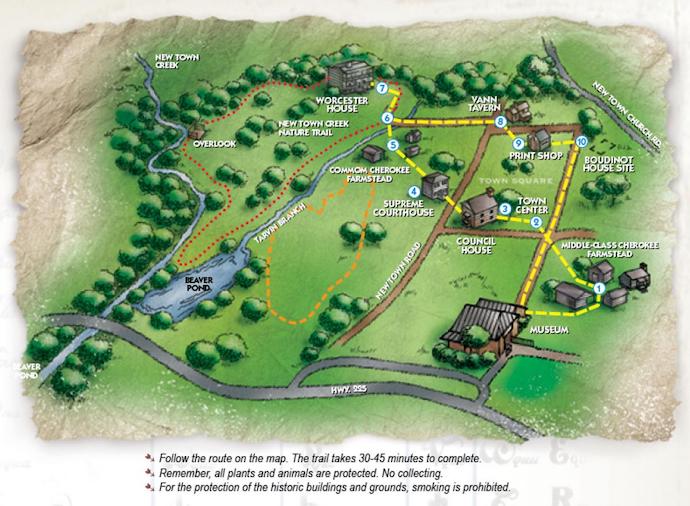

Exploring the New Echota Historic Site

You’ll start your tour of New Echota at the park’s Visitors Center.

It’s really worth taking the time to check out the small museum there before exploring the 12 original and reconstructed buildings on the historic site’s expansive grounds.

The interpretive exhibits and 17-minute film here offer an excellent introduction to the history of the Cherokee people, their culture, and their community in the town of New Echota.

There’s a lot of info about the state of Georgia’s land grab… er, “Land Lottery.” There are also exhibits on the legal maneuvering behind the Cherokee’s fight to retain their autonomy, the Treaty of New Echota, and the Trail of Tears.

All of this information really helps to make your experience at New Echota more meaningful, bringing this colonial history to life in much greater detail than this story can aspire to.

Note that you can also use a smartphone at areas along the New Echota property to listen to an audio guide, and there are hand-cranked audio stations that offer additional insights on the town.

READ MORE: Visiting the Expedition Bigfoot Museum in Cherry Log GA

Cherokee Farmstead

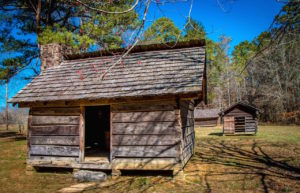

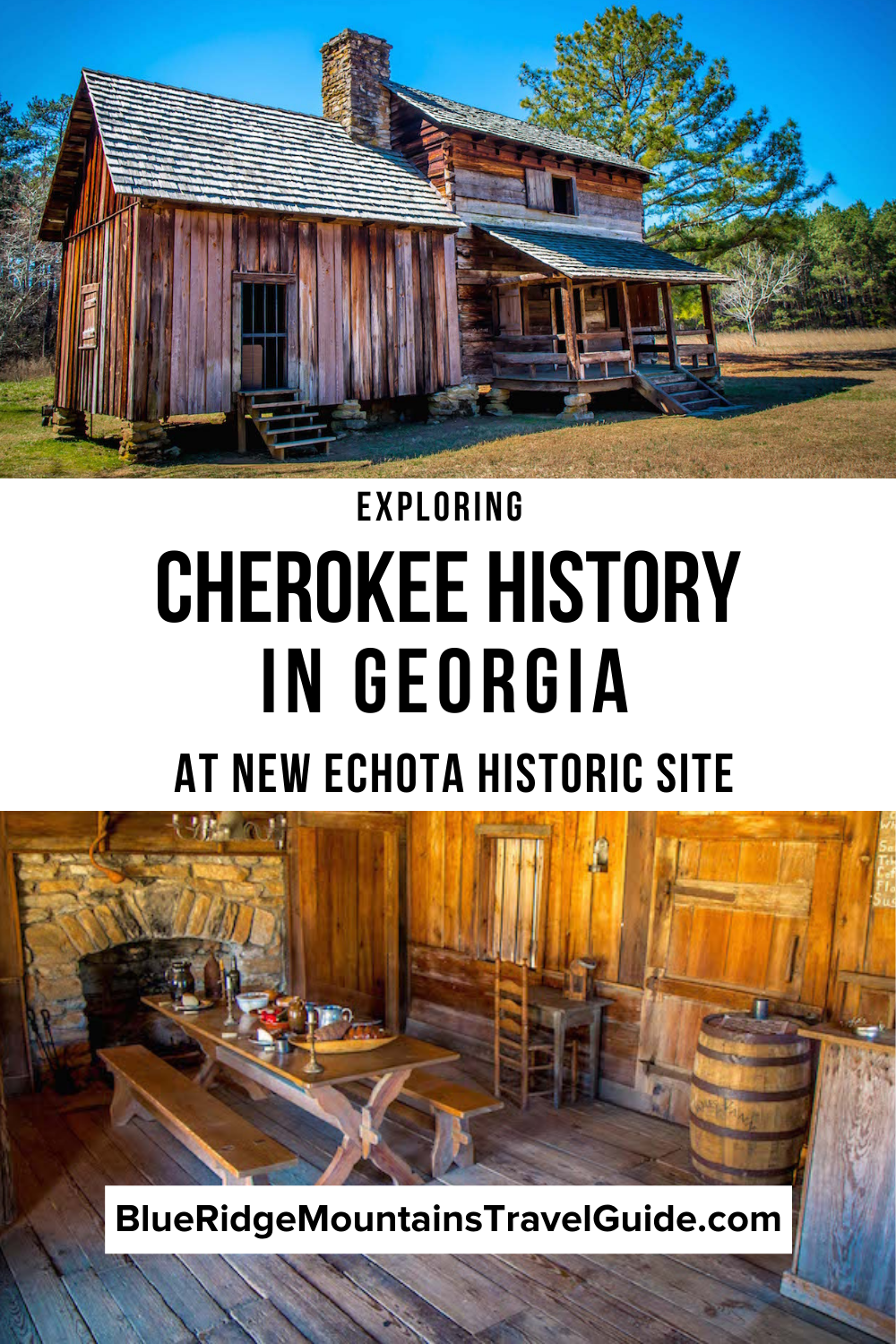

Once you head outside, the first set of buildings you’ll see depict a typical early 19th century Cherokee Farmstead.

It consists of a simple cabin, a small smokehouse, a corn crib (for storing the harvest), and a large barn. This fenced compound would also usually consist of a substantial garden.

Note the traditional Cherokee style of log cabin craftsmanship of these buildings. By 1837, there were more than 6,000 of these types of buildings built by the Cherokee of Georgia alone.

On the backside of the cabin you can get a look inside this traditional middle class cabin.

The bed, table, spinning wheel, butter churn, and other elements are all typical of their time, while the rivercane blowgun, ball sticks, and handmade crafts are pure Cherokee culture.

READ MORE: The 10 Best Places for River Tubing in North Georgia

Cherokee Council House

The Cherokee Nation built its council house at “New Town” in 1819, before the seat of government was officially moved to New Echota.

Major Ridge, one of the most prominent Cherokee leaders of the early 1800s, led the very first processional of tribal officials into the Council House.

The Council House was located at the center of the community, which was divided into a series of streets and lots.

From 1819 to 1835, this was arguably the single most important building in the entire Cherokee Nation.

READ MORE: The 20 Best Places to Live in the Georgia Mountains

Cherokee Phoenix Printing Office

It would be difficult to overstate the cultural impact of Sequoyah‘s creation of the Cherokee Syllabary, the written form of the Cherokee language.

The Cherokee Phoenix, which was written (in Cherokee and English) and printed in a tiny shop in the heart of New Echota, was the primary vehicle for getting news about the tribe to the masses.

The printing office you see here today is a reconstruction of the 1827 original, which printed newspapers as well as books that were translated into Cherokee.

The circa 1870 printing press is also very similar to the original, from which some 1,500 pieces of lead printing type were discovered during a mid-20th century archaeological excavation of the New Echota site.

READ MORE: The 15 Best Things to Do in Blue Ridge GA

Supreme Courthouse

Located directly across New Town Street from the Council House and Printing Office, this two-story house was home to the Cherokee Nation’s Supreme Court.

With one courtroom on each level, this is where many of the tribe’s important legal matters were adjudicated.

Inside it looks very much like the courtrooms of today, with an elevated bench at one side and plenty of public seating.

READ MORE: The Best Things to Do in Clayton GA

Common Cherokee Farmstead

The disparity between the middle class and common Cherokee homes proves striking when you reach this little homestead at New Echota.

The Cherokee culture traditionally only allowed each family as much land as they could capably farm. So smaller families got less land, and had smaller houses.

The tiny log cabin here is still very well-made. But it lacks all but the most basic amenities– a small bed, simple log-base table, stool, and an animal pelt as the only decor.

Where the middle class house boasts a sizable barn, this one has just a small stable and corn crib, with no smokehouse.

READ MORE: The Roundhouse Rental Cabin in Helen GA

Vann’s Tavern

The son of a mixed-race Cherokee woman and an Indian trader, Chief James Vann was a prominent Cherokee leader aligned with Major Ridge and Charles Hicks. The trio believed the Cherokee people needed to acculturate in order to deal with the European settlers and the United States government.

Vann was a savvy businessman and arguably among the wealthiest men in America at the dawn of the 19th century. In addition to lucrative land deals, trading posts, and a ferry across the Chattahoochee River, the Georgia native also owned numerous taverns and stores across the state.

Vann’s Tavern at New Echota was relocated to the site from Forsyth County. Much of the early 1800s building is original, though modern nails and wood were used in its restoration.

Inside you’ll find a typical tavern/inn of the era, which would have a small bar, picnic table for dining, and small rooms for rent upstairs. It’s interesting to note that a room for the night was just 50¢, while a shot of whiskey was 25¢!

READ MORE: The 13 Best Restaurants in Blue Ridge GA

The Worcester House

Set along New Town Creek, the Worcester House is the only original building at New Echota to survive relatively intact. It was constructed in 1828 by missionary Rev. Samuel A. Worcester, who staunchly stood for Cherokee sovereignty.

The house, which served as the Worcester family home as well as the New Echota Mission Station, boasts New England features such as a central fireplace used for both heating and cooking.

The four rooms on the second floor were used for visitors and boarders, with an outside stairway allowing for private access. One room contains an original loom and spinning wheel, which most Cherokee homes of the time would have.

The Worcesters, who were extremely sympathetic to the plight of the Cherokee, were forced out of their home in 1834 by a local who had gained rights to it via the Georgia Land Lottery.

The home was occupied by various residents until 1952, and restored to its former glory in 1958-59.

READ MORE: The 15 Best Lakes in the North Georgia Mountains

Beaver Pond Trail & New Town Creek Nature Trail

As you make your way back to the Worcester House, you’ll cross over a small branch of New Town Creek. This area is where hundreds of Cherokee would make camp during major council meetings and other significant events.

Today there’s a lovely New Town Creek Nature Trail to explore. The 1.2-mile loop trail is interpretive, with signs explaining more about then flora and fauna you’ll see, as well as an overlook of the creek that makes a great birdwatching spot.

For a longer walk, there’s also a Beaver Pond Trail that starts at the Common Cherokee Farmstead and follows the creek branch back to, you guessed it, a lovely little beaver pond.

Note that this flat plain does tend to flood a bit after heavy rains. And while dogs are allowed in New Echota State Park on a leash, we’ve heard reports of heavy tick activity in the woods. So proceed with caution! –by Bret Love; all photos by Bret Love & Mary Gabbett; portraits via Public Domain