In the late 1820s, gold was discovered in North Georgia near the mountain towns of Dahlonega and Helen.

This discovery– the first major gold rush in the US (after a smaller discovery in North Carolina)– led to an influx of prospectors, all looking to find their fortune by gold mining in Georgia.

The Georgia Gold Rush lasted for more than a decade, from 1829 to the early 1840s. By 1831, there were an estimated 6,000 to 10,000 miners working between the Etowah and Chestatee Rivers alone.

The increased population caused by the desire to make money from exploiting the state’s natural resources ultimately led to the removal of the Cherokee and Muskogee (a.k.a. Creek) Indians.

These Native American tribes in Georgia had been here for hundreds of years before the settlers arrived.

Yet they were forced out of their ancestral homes by mining companies and the U.S. government in favor of European immigrants looking to purchase land.

Tensions gradually rose in the 1830s, until the Cherokee people were removed via the Trail of Tears in 1836.

Read on to learn more about the connection between gold mining in Georgia and the Trail of Tears, including a detailed history of the Georgia Gold Rush and the Treaty of New Echota.

READ MORE: Exploring Oconaluftee Indian Village & Visitor Center in Cherokee NC

Gold Mining in Georgia, Land Lotteries & Trail of Tears Guide

- The Discovery of Gold in Georgia

- The Georgia Gold Rush

- Georgia Land Lotteries

- The Treaty of New Echota

- The Trail of Tears in Georgia

The Discovery of Gold in Georgia

In 1829, The Georgia Journal in Milledgeville ran a story on the groundbreaking discovery of gold in Georgia, which would have a major impact on Georgia’s state history.

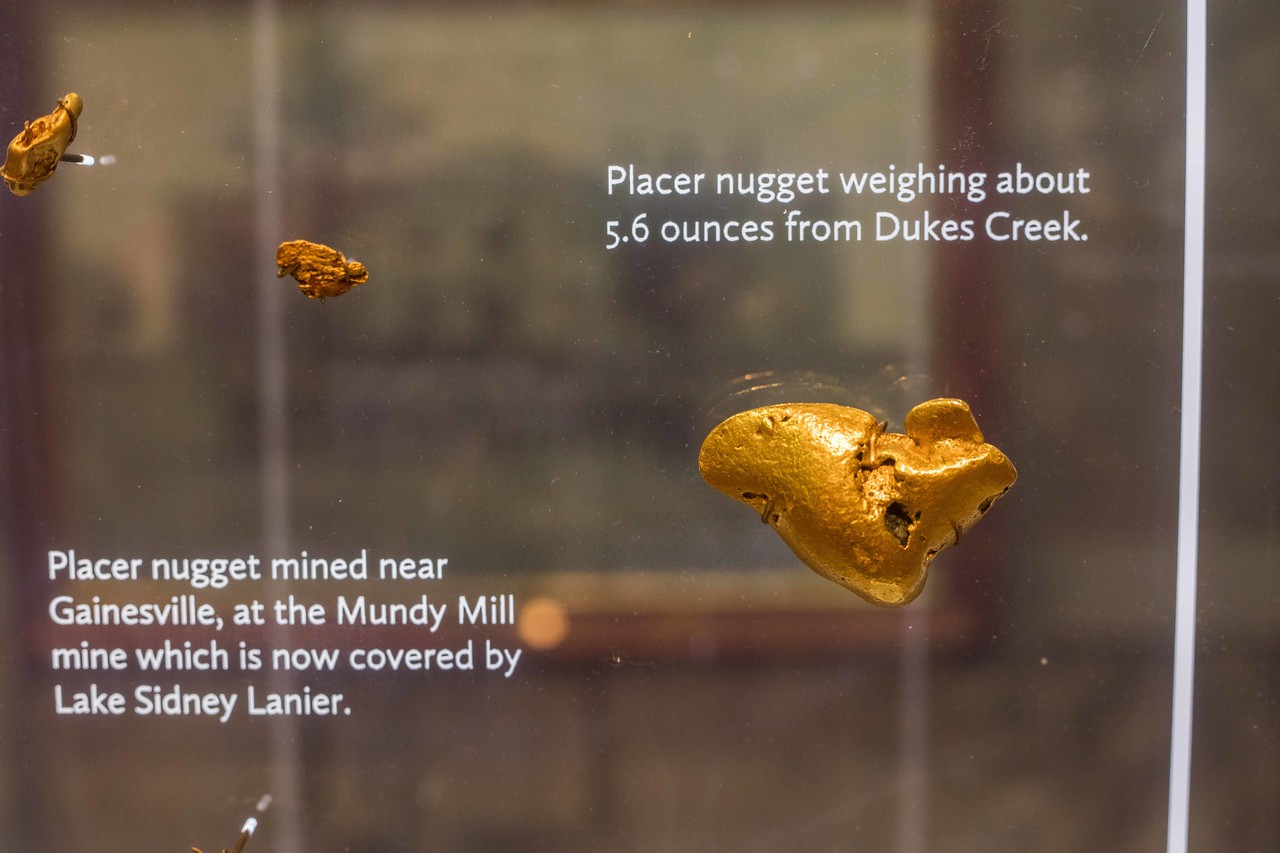

Gold was discovered in 1828, in Wards Creek (near Dahlonega) and Dukes Creek (near Helen). To this day, it remains a matter of great debate who discovered it first, and where.

Six different individuals made claims that they were the ones who discovered Georgia gold, but no documented evidence exists to support any of them.

According to the most popular story, a man named Benjamin Parks was out hunting deer when he tripped over a rock. Upon closer inspection, he realized that the rock was full of gold.

Of course at that time the Cherokee people still occupied much of the land where the gold was found. So it’s entirely possible that they’d found gold in Georgia long before the European settlers arrived.

In fact, the word Dahlonega (the inarguable epicenter of the Georgia Gold Rush) comes from a Cherokee word for “gold” or “the place of yellow metal.”

The Cherokee mined the area as well, using the same gold panning techniques as the white settlers. Soon after the discovery of gold in Georgia, stories of gold in the Cherokee Nation spread north along the east coast.

Miners from all over the country rushed to present-day Dahlonega, hoping to claim a piece of the action themselves.

READ MORE: The 20 Best Things to Do in Dahlonega GA & Lumpkin County

The Georgia Gold Rush

The Georgia Gold Rush came 30 years after the North Carolina Gold Rush of 1799.

Locals in the Blue Ridge mountains had long held hopes that the gold veins would extend down into North Georgia, and eventually their prayers were answered.

It’s estimated that nearly 15,000 miners made their way into the North Georgia mountains after learning about the discovery of Georgia gold.

Many of the miners (most of whom were single white men) chose to settle in Lumpkin County. Their desire for lands upon which to build homesteads ultimately led to the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

Signed into law by Andrew Jackson, the Act authorized the President to grant lands west of the Mississippi to Native Americans while seizing ancestral Indian lands within existing state borders.

There were also Georgia state laws put into place to restrict the Cherokee. The indigenous people weren’t allowed to meet for legislative purposes or defend themselves in court.

The Cherokee people were also forced to abandon their mines and gold panning in Georgia once larger mining operations moved in. Prospectors often resorted to physical violence to stop the Cherokee people from mining.

By 1849, the Georgia gold rush had ended. Profitable gold veins became harder and harder to find, leading to increasingly dangerous working conditions.

Many of the miners ultimately chose to relocate to California, following news of gold in the Sutter’s Mill area. Others stayed and established Georgia farms to grow cotton, fruit, and other crops.

But gold mining in Georgia is still a popular tourist activity today. Visitors can tour the Consolidated Gold Mine in Dahlonega, or try their hands at panning for gold in local creeks and stream beds.

READ MORE: The 15 Best Cabin Rentals in Dahlonega GA

Georgia Land Lotteries

Soon after the Revolutionary War ended, the state of Georgia began issuing land grants to families, hoping to give common citizens more power.

Large companies were purchasing huge parcels of land in the state via bribery, and the Georgia legislature was tired of all the corruption.

They were also hoping to bring more people to the state, to increase its representation in Congress.

To that end, they created a land lottery in Georgia, which consisted of eight separate lotteries that were held between 1805 and 1833. All white, male citizens of the state could enter their names for a chance to win plots of land.

These parcels, which were stolen from the Muscogee and Cherokee tribes over time, generally ranged from 40 to 500+ acres, depending on the lottery.

For just 4 to 7¢ an acre, they could purchase this stolen land and use it to mine for gold, or start their own farms. The indigenous people living on the land had to abandon their crops, mining activities, and ancestral lands.

They took the issue all the way to the Supreme Court, in the case of the Cherokee Nation v. Georgia. But the Supreme Court refused to recognize the authority of their nation until the second case, Worchester v. Georgia.

The Supreme Court’s ruling in the second case made the Indian Removal Act invalid. But President Andrew Jackson and the State of Georgia decided to ignore the ruling entirely.

Instead, they began enforcing the removal of the Cherokee in Georgia, North Carolina, and beyond.

READ MORE: The 7 Best Restaurants in Dahlonega GA for Foodies

The Treaty of New Echota

Five years after the Indian Removal Act was signed, the Treaty of New Echota was signed in 1835. This treaty directly led to the forced removal of the Cherokee and Muscogee Indians on what became known as the Trail of Tears.

Cherokee tribal leaders led by Major Ridge and his son, John, met with U.S. Government officials in New Echota (near present-day Calhoun GA).

These members of the Cherokee Council claimed to represent their entire tribe, but in fact were the members of a minority party that only represented around 500 people.

Known as the Treaty Party, this vocal minority believed they could secure rights for the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma. So they signed the treaty and gave up their ancestral lands in exchange for land out west and $5 million.

The treaty also included a clause allowing some members of the Cherokee Nation to become citizens and landowners in Georgia. The clause was removed by Andrew Jackson after the agreement had been approved by the Treaty Party.

After it was ratified by the United States Senate and signed into law by President Jackson, many of the Cherokee people gathered at New Echota, determined to fight the treaty in court.

They argued that the Treaty Party had acted against the wishes of the tribe’s majority, but they were denied.

Despite having a petition with almost 16,000 signatures on it, their voices went unheard. Within a year of the treaty being signed into law, the tragic Trail of Tears in Georgia began.

READ MORE: The 15 Best Historic Sites in Georgia

The Trail of Tears in Georgia

The Trail of Tears in Georgia is the path that some 16,000 Indians used in their forced removal to Oklahoma between 1836 and 1839.

Their removal was brutally inhumane, with many people being killed or dying of disease, exhaustion, or starvation along the 1,000-mile journey.

They were often forced to walk in bad weather, or wait in Chattanooga internment camps while deadly diseases spread among the masses.

Eventually, Chief John Ross managed to secure his position as leader of the reluctant removal. He organized wagon trains with physicians and interpreters, and a steamboat for himself and other tribal leaders.

While there were still many problems, his actions drastically lowered the number of people who died on the way to their new land.

Named “the place where they cried” by the Cherokee People, the Trail of Tears is a National Historic Site that deserves to be remembered.

There are many ways to visit the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail in Georgia, and learn more about the history of the Cherokee Nation.

The trail passes through many different small towns in North Georgia, including Rome, Dalton, Canton, Calhoun, Fort Oglethorpe, Chatsworth, Cedartown, and Cave Spring.

If you want to learn more about the Trail of Tears, the New Echota State Historic Site in Calhoun, the Chief John Ross House in Rossville, and the Chattanooga & Chickamauga Military Park are all great places to visit. –by Amy Lewis; lead image via Canva